Program: #19-24 Air Date: Jun 03, 2019

To listen to this show, you must first LOG IN. If you have already logged in, but you are still seeing this message, please SUBSCRIBE or UPGRADE your subscriber level today.

Note: For this month we share interviews from our recent journey to England celebrating some of the great conductors and ensembles.

Our friend Andrew Carwood of the Cardinall’s Musick is back with his latest two works: Votive Antiphons of Thomas Tallis, and the composer who is a link to (and possible teacher of) William Byrd, Robert Parsons.

NOTE: All of the music on this program is from the recordings featuring The Cardinall’s Musick directed by our guest Andrew Carwood. For more information on this ensemble: http://www.cardinallsmusick.com/

I & III. Robert Parsons (c.1535-1572). Hyperion CD CDA67874.

The Cardinall’s Musick continue their recording success with their latest disc of the music of Robert Parsons. Most famous for his setting of the Ave Maria, the recording proves that the composer was far from being a one-hit-wonder!

Fabrice Fitch, writing in Gramophone, says “Carwood and his singers make a case for Parsons… it’s worth buying this disc just for this object lesson in word painting…. The Cardinall’s Musick are at their best in this repertoire, and their performances have confidence and authority… Parsons certainly deserves the hearing that Carwood’s musicians afford us, so this addition to the catalogue is very valuable”. Editor James Inverne has gone further, making the disc ‘Editor’s Choice’ in the November issue.

In BBC Music Magazine, Kate Bolton give the recording 5 stars, saying: “Having previously explored English polyphony at the extremes of the 16th century – Cornysh, Fayrfax and Ludford at the beginning, Byrd at the end – The Cardinall’s Musick now bridges the gap with the enigmatic mid-century composer Robert Parsons. He lived through some of the most turbulent years of England’s religious and political history, and his life was tragically cut short when he drowned at a young age. So, while there are some serene works here, with soaring melismatic lines that hark back to the music of the Eton Choirbook, most of these pieces are sonorously scored for low voices and peppered with bitter dissonances, giving them a dark, plangent quality. Director Andrew Carwood draws earthy, visceral performances; the ensemble’s virile sound and Parsons’s sinewy polyphony are a far cry from what some critics describe as the ‘whitewashed’, English choral tradition. Carwood and his singers highlight the inherent drama of Parsons’s style, notably in O bone Jesu, with its changing textures, brilliant canons and expressive dissonances. The basses resonate magnificently in Peccantem me quotidie, in Holy Lord God Almighty and in the hauntingly austere Libera me, while, by contrast, the monumental Magnificat sounds radiant. Perhaps the crowning glory of the disc is the final Ave Maria, the slow and poignant unfolding of which echoes long in the memory. Hyperion’s detailed recording, swathed in the glowing acoustic of the Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel Castle, enhances these seraphic performances.”

Rebecca Taverner from Choir and Organ notes that “the recording has deep perspective and clarity with the sequence of works, mostly scored for low voices, given fluid impassioned readings, with vibrant bass sonorities providing and almost instrumental foundation… tonal beauty, impeccable ensemble and blend”.

Lack of information about a composer is a common problem for the researcher of early music, especially in sixteenth-century England where so many records have been lost. Add to this a seemingly early and unusual death and a mournful personal note from a contemporary collector of sacred music and Robert Parsons proves to be even more fascinating than most of his contemporaries.

Robert Parsons is first found in a Teller’s Roll for 1560/1 which refers to him co-ordinating payments to Richard Bower, Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal. The Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal records Parsons’ appointment as a Gentleman on 17 October 1563:

Merton died 22nd of September, and Roberte Parsons sworne in his place the 17th October, Ao 5to.

Unusually there is no note of the place where he had previously been employed and this, together with the references in the Teller’s Roll, suggests that Parsons was connected with the Chapel before he became a Gentleman. On 30 May 1567 he was granted a Crown lease for twenty-one years on three rectories near Lincoln (‘Sturton, Randbie and Staynton’) and in 1571 an annual tax certificate issued to court servants confirms his residence as being in Greenwich. The next mention is a further emotionless reference in the Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal:

Robt. Parsons was drowned at Newark uppon Trent the 25th of Januarie, and Wm. Bird sworne gentleman in his place at the first the 22d of Februarie followinge, Ao 14o Lincolne.

Quite why he was travelling near Newark is unclear. He may have been visiting his rectories or attending to other business but it is clear that he died in 1572, the fourteenth regnal year of Queen Elizabeth I. His only epitaph is a couplet found in the partbooks prepared by the copyist Robert Dow in the 1580s which suggests that Parsons was highly esteemed and suffered an early death:

Qui tantus primo Parsone in flore fuisti

Quantus in autumno ni morere fores.

[Parsons, you who were so great in the springtime of life,

how great you would have been in the autumn, had death not come.]

Parsons lived through some of the most tumultuous years of the sixteenth century as the four religious settlements loosely termed the English Reformation tore society apart. After Henry VIII’s break with Rome and his relatively conservative reforms, the baton was then passed in 1549 to his son Edward VI who, steered by his Protestant advisors and then later developing his own agenda, pursued a more radical path. This course was halted by Edward’s half-sister, Mary I, eldest daughter of Henry VIII and devout Catholic, in 1553. She returned England to communion with Rome and met with much support for her policies until the economic downturn of the late 1550s and her own increasing personal instability. Then in turn her death in 1558 and the accession of Elizabeth I, her half-sister and Henry’s second daughter, led to a new English settlement which drew on Edward’s reforms but with considerably more artistic and liturgical sensitivity than had been allowed by the young king.

The surviving music by Parsons consists of nine pieces in Latin, two Services in English, two anthems in English, a handful of secular songs and some instrumental pieces including five In nomines. The lack of small-scale English sacred music seems to suggest that Parsons was not active as a composer during the reign of Edward VI. His earliest work is probably the opulent setting of the Magnificat which harkens back to a tradition seen clearly in the Eton Choirbook and which was developed by Robert Fayrfax, Nicholas Ludford and John Taverner. Five Magnificats in the Forrest-Heyther Partbooks and the Office Hymns by Tallis and Sheppard seem to suggest that Mary was keen to reinstate large-scale music at the Office of Vespers. The lack of accompanying Nunc dimittis settings suggest these Magnificats were designed specifically for Vespers rather than the reformed Evensong when both Canticles would be required.

Parsons’ setting uses a traditional alternation of plainsong and polyphony and is scored for six voices, sometimes with lengthy divisions or ‘gimells’, but this is no mere exercise by a young composer trying to find his feet. That Parsons has a sophisticated grasp of compositional techniques is seen most clearly in his use of canon (where one or more parts will repeat exactly a melody sung by an opening voice). These can be found in the sections ‘Quia fecit mihi magna’ (at the octave between triplex and contratenor II), ‘et sanctum nomen eius’ (at the ninth between tenor and medius), ‘et semini eius in saecula’ (at the tenth between bassus and medius) and at ‘Sicut erat in principio’ (a three-part canon at the unison between the two contratenors and at the octave with the triplex). Although Parsons is obviously drawing on older models, his setting seems less archaic than that by Robert White. There is no reliance on cantus firmus and the plainchant melody is given only slight attention in the polyphonic verses. Parsons does however preserve the use of melismatic writing for the solo lines and contrasts these with more massive full-choir sections.

Two important characteristics can be seen in this piece, both of which were later to reach their zenith in O bone Jesu. The first is an enjoyment of symmetry and development. In the Magnificat the various canons (imitation at the octave, the ninth, then tenth and culminating in the three-part canon at the unison and octave) have an obvious sense of progression. The second is a remarkably sophisticated understanding of the dramatic potential of the final section of an extended piece. It can be seen clearly in the ‘Amen’ where the bass and tenor parts are engaged in a dialogue which constantly reiterates their themes whilst the other parts weave a polyphonic web above them.

Solemnis urgebat dies (‘Iam Christus astra ascenderat’) is the Office Hymn at Matins on the Feast of Pentecost. It is similar to settings by Sheppard and Tallis where plainsong alternates with polyphony, the stanza structure is rigorously preserved, all movement is virtually syllabic and the plainsong cantus firmus is quoted exactly in the upper voice.

Queen Mary did not want a wholesale return to some perceived halcyon age but was intelligent enough to realize that she had to provide a settlement which did not ignore the recent past. As composers grappled with this new reality they had to find suitable texts for any extended compositions as there seemed to be no demand for a return to the old-fashioned and lengthy Votive Antiphons to the Virgin Mary. They turned instead to the Book of Psalms and to two Psalms in particular—Psalm 15 (or 14 in the Vulgate) Domine, quis habitabit? and various portions of the extended Psalm 119 (Vulgate 118). Both texts are concerned with righteous living and the following of God’s commandments and instruct people how to live a godly life. Could it be that these texts became popular for people searching for the ‘right’ way? The to-and-fro of politics had created a considerable degree of confusion and unease and such advice could be invaluable. Or was it that such texts could apply equally to Protestants as well as Catholics and were unlikely to cause offence?

Domine, quis habitabit? was set by Tallis, William Mundy, Robert White (three times) and William Byrd as well as Parsons himself. Parsons sets only the first half of the Psalm (as does Byrd) and makes a feature of juxtaposing the high voices against the lower ones. The piece seems to owe more to the Continental Flemish style than his more florid English inheritance and this becomes clear when it is compared with Retribue servo tuo, a setting of the third portion of Psalm 119. There are a further eight contemporary settings of these verses: one by Christopher Tye, three from William Mundy and four from White. Parsons’ setting is reminiscent of the old Votive Antiphon style, starting with just three voices before expanding briefly to four parts, then back to three and then four, before the first full-choir entry at ‘Increpasti superbos’. Similarly, the second section begins with a trio before moving to a quintet with a bass gimell before the final full section. It is rare to find detailed expression of text in Votive Antiphons (Fayrfax’s Maria plena virtute being a notable exception) but the full-choir flourishes could often be used for dramatic effect either to underline the importance of a portion of text or a particular word. Parsons divides the Psalm unequally with five verses in the first section and only three in the second and thus highlights the following verses with full choir writing:

Increpasti superbos,

maledicti qui declinant a mandatis tuis.

[You have rebuked the proud,

cursed are they that do err from your commandments.]

and:

Nam et testimonia tua meditatio mea est,

et consilium meum iustificationes tuae.

[For your testimonies are my delight,

and your judgments my counsellors.]

Once again Parsons’ control of drama is evident with his imaginative use of the solo sections, fooling the listener into thinking that the full choir is about to enter only to continue with differently scored solo writing. He provides a short but masterful ‘Amen’ coda, choosing a dotted subject for imitation which impels the listener forward to the final cadence. Parsons also shows his fascination with the interval of a seventh, one that needs some form of cloaking in order to sound acceptable to sixteenth-century ears. This he achieves by breaking the interval in two, most often a third followed by a fifth, or vice versa (‘non abscondas a me’, ‘a mandatis tuis’, ‘servus autem tuus’ and ‘meditatio mea est’).

The unusual setting of O bone Jesu for five voices also draws on the tradition of the old Votive Antiphon. This text had proved a puzzle for academics being a seemingly random selection of Psalm verses each concluding with an invocation to Jesus. It bears no relation to other settings which begin with the words ‘O bone Jesu’ and Parsons is the only English composer to assay these words. It was David Skinner who solved the riddle when he came across the reference to ‘St Bernard’s Verses’ in various Primers and Books of Hours, one of which contained the following rubric:

When St Bernard was in his daily prayers, the devil said unto him. ‘I know that there be certain verses in the Psalter, who that say them daily shall not perish, and he shall have knowledge of the day that he shall die.’ But the fiend would not show them [to] St Bernard. Then St Bernard [answered] ‘I shall say daily the whole Psalter.’ The fiend, considering that St Bernard shall do so much profit to labour so, he showed him these verses.

This was just the sort of devotion ridiculed by Erasmus in In Praise of Folly (1511) and condemned by Archbishop Cranmer in his Homily of Good Works (1547). O bone Jesu must be considered Parsons’ highest dramatic achievement. The piece sets full-choir writing (mainly for the invocations of Christ) against solo sections for the Psalm verses. His sense of symmetry is clear from the outset, starting with a duet, then increasing to a trio and then a quartet before the entry of the full choir signals the end of the first section. A trio starts the second section giving way to a sextet with a bass gimell (as in Retribue) with both bass voices in canon at the unison. The text ‘Clamavi ad te, Domine’ (‘I have cried to you, Lord.’) elicits an irresistible scale starting on a low F and moving up by step to a fourth above the octave—perhaps a clever cross reference to Psalm 130 ‘De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine’ (‘Out of the deep have I cried to you, Lord’) with the bass voices rising from the depths to the heaven with their cry. This canon allows an intensification of the drama and cleverly creates a ‘battle’ tension between the two bass voices impelling the music forward to the full-choir explosion at ‘O Rex noster’. The tension then recedes as the full choir moves into the final verses and increases gradually towards the final ‘Amen’ where Parsons returns to ‘battle’ between the voices, increasing the pitch one step at a time until the final eight bars where the constant hammering of the tonic note D on the weak beats of the bar allows the final cadence to feel one of total relief and fulfilment.

Yet another link between composers of the mid-sixteenth-century is their penchant for producing sets of Lamentations and Responds from the Office of Matins in the Funeral Rite. No Lamentations have survived from Parsons but settings were produced by Tallis, Osbert Parsley, White (two sets), Alfonso Ferrabosco and Byrd. It is interesting to note these names when looking at the three Funeral Responds set by Parsons, as three similar Responds are set both by Alfonso Ferrabosco and William Byrd. Libera me, Domine (9th Respond) is an austere work with the plainsong cantus firmus maintained throughout in the tenor part. It is likely that Parsons’ setting was the model for one by William Byrd published in his 1575 Cantiones Sacrae. Peccantem me quotidie (7th Respond) sounds more modern even though it carries the plainsong tune as a cantus firmus in the contratenor I part; its lines are smoother and there is more step-wise movement in the melodies and a greater reliance on plangent harmonies. Credo quod redemptor (1st Respond) sounds the most modern of the three as its style is more reminiscent of the early Elizabethan motet as developed by Tallis and Byrd. There are striking similarities between this piece and a setting of the same text by Alfonso Ferrabosco and it has been suggested that Ferrabosco, originally a native of Bologna who was resident in England at various times in this period, had brought the idea of setting the Funeral Responds from the Continent. However, if this is the case it seems odd that Parsons should have set two such Responds using the old-fashioned cantus firmus technique. Parsons’ characteristic broken sixths and sevenths are obvious in the opening bars of Credo quod redemptor and it seems more likely that Parsons was the model for Ferrabosco.

Deliver me from mine enemies and Holy Lord God Almighty are definitely influenced by the Flemish style from the Continent. They are full throughout and the text-setting is efficient although with no hint of the Edwardine style where homophony is the norm. Both pieces rely heavily on close imitation, especially Deliver me from mine enemies which is based on a canon between the two highest voices. Holy Lord God Almighty does use the Edwardine form of ABB which is found in short anthems by Tallis, Sheppard and others but its rather instrumental style clearly places it as an Elizabethan piece.

Ave Maria has become Parsons’ most famous and well-loved motet since it was included in the Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems in 1978. Settings of the Ave Maria are not frequent in England—even William Byrd only set them as required by the liturgy in his two books of Gradualia (1605 and 1607) rather than as stand-alone pieces. Parsons simply sets the lines found in the Gospel of St Luke and has no invocation for the dead (authorized by Pope Pius V in 1568). This is a magical setting and it is not surprising that there is a beautiful ‘Amen’ coda. Initially the piece gives the impression of using a cantus firmus in the top part but it is in fact free-composed throughout. Parsons starts each medius phrase one note higher than the previous one, beginning on F and then moving up to D with long slow notes before reaching ‘benedicta tu’ when it joins the other voices in equal importance. Paul Doe has suggested that this piece might have been prompted by the early promise or subsequent plight of Mary, Queen of Scots. There is no direct evidence for this but it is not unreasonable to consider Parsons and indeed most of the mid-sixteenth-century writers—Sheppard, Tallis, White, Mundy and Tye—as Catholic sympathizers. They seem more free, more expressive, more expansive and more brave in their Latin compositions and it is tempting to speculate that in setting words from Psalms 15 and 119, the Lamentations and the Funeral Responds, they were consciously producing music with a Catholic slant. In comparison their English works tend to be shorter and less virtuosic and even the fledgling Great Services are short on excellent material, but then these mid-sixteenth-century composers were creating a new genre not previously explored and were probably writing to fulfil a set of rules which were not entirely clear. England had to wait for another generation—headed by William Byrd, Thomas Weelkes and Thomas Morley—before writing in English could achieve greatness.—Andrew Carwood

1 Domine, quis habitabit? 5:12

2 Peccantem me quotidie 3:44

3 Holy Lord God Almighty 3:48

4 Deliver me from mine enemies 2:39

5 Retribue servo tuo 8:04

6 Solemnis urgebat dies 5:39

7 Magnificat 13:15

8 Libera me, Domine 7:31

9 Credo quod redemptor 3:32

10 O bone Jesu 11:42

11 Ave Maria 4:56

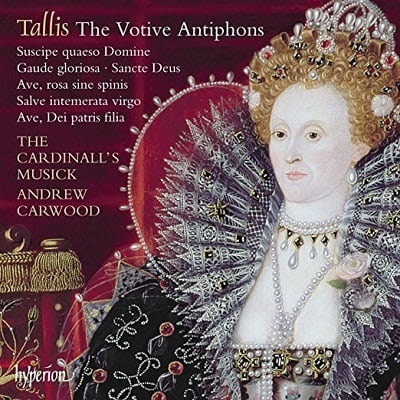

II. Tallis: The Votive Antiphons Hyperion CD CDA68250.

From MusicWebInternational.com: Tallis’s long life spanned the reigns of all five Tudor monarchs. Consequently he had to endure four major shifts in styles of worship, from the pre-Reformation Sarum rite in Latin (the Salisbury usage which was widely popular), the limited Henrician reforms, the drastically simplified rite in English under Edward VI, then a brief return to Sarum under Mary before the victory of Protestantism and the English rite under Elizabeth. He seems to have been a modest and unassuming man who made the best of his situation. He is remembered for his work in getting music for the English rite going, but it seems that his heart was really in the older forms. His best music is to the Latin rite. We should also remember that Elizabeth, although necessarily a Protestant, was fond of Latin church music and enjoyed it in the Chapel Royal. Both Tallis and his later colleague and successor Byrd remained Catholics and were protected by the queen.

Here we have a collection of his votive antiphons. These were free compositions, often of considerable length, usually setting specially written texts honouring the Virgin Mary, and sung after the last service of the day. They were written in the elaborate style which was used for the Sarum rite, with frequent melismas – several notes to a syllable – whereas the Reformers preferred syllabic settings in which the words were clear and distinct. They were consequently popular before the Reformation and frowned on afterwards.

Strictly speaking, two of the pieces here, the first and last, are not votive antiphons but motets. However, there is no need to quibble. These two are also probably the latest to be written. Suscipe quaeso Domine comes from the 1575 Cantiones sacrae volume which Tallis published together with Byrd. Each composer contributed seventeen pieces, possibly to mark the seventeen years since the queen’s accession. However, this piece was quite possibly written for use under Mary, for the occasion when Cardinal Pole absolved England from schism in 1554. It is clear and passionate, easy to follow and powerful.

Gaude gloriosa, possibly the last, and certainly the longest and the most splendid of Tallis’s votive antiphons, also probably comes from the brief period of Marian restoration. It is written for six rather than the more usual five voices, and some of these lines are sometimes split, making for a really rich texture. It also has that onwards propulsion which is a mark of Tallis’s best work, with flexible long lines.

The next four works are all early, dating from the Henrician period, and are somewhat less accomplished, being inclined to sprawl. Salve intemerata is possibly the worst offender here, and is one of Tallis’s earliest surviving compositions. A particular point of interest is that Ave, rosa sine spinis and Ave, Dei patris filia do not survive intact. The first has a missing passage in the treble line, which has here been reconstructed by Nick Sandon, and the second also has missing passages which have been reconstructed by David Allinson. It is a wonderful thing that it has been possible to make these works performable in this way. All these pieces are of interest and you can hear Tallis developing his long lines, increasingly assured harmony and wonderful variety of texture.

Finally we have O nata lux, from the 1575 Cantiones sacrae, which sets two verses from the hymn at Lauds on the feast of the Transfiguration. This is a motet rather than a hymn setting, and the other verses from the hymn play no part. It is a late work, a tiny piece, but a gem. Tallis here shows himself as accomplished in the newer style of music as he had been with the votive antiphons of earlier periods.

The Cardinall’s Musick is a mixed choir with women on the top line. It has a long and distinguished track record in Tudor Latin church music, with their complete recording of Byrd’s Latin works (originally ASV and then Hyperion) a particular highlight. Their performances here are as secure and eloquent as one would expect, and they bring plenty of variety to what could be rather long-winded texts. This disc has been compiled from five of their previous seven discs of Tallis for Hyperion, with recording dates ranging from 2005 to 2014. However, all recordings were made in the sympathetic acoustic of the Fitzalan Chapel at Arundel Castle by the same team and, not surprisingly, they match well on this compilation.

There are other recordings of the music here, though sometimes not many. The chief competitor is the Chapelle du Roi under Alistair Dixon, who have recorded Tallis’s complete works on nine discs (Signum). However, you would have to buy several, or the whole set, to get all the works here, as you would with the original issues of these performances. So this is a convenient way of exploring votive antiphons on one disc. Texts and translations are included, as are details of the singers for each work and helpful notes on the music and the whole production is exemplary.

Stephen Barber

Composers of the early sixteenth century in the main set texts for three different liturgical functions: the Ordinary texts for use during the Mass (Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei); the Magnificat for use during Vespers; and devotional texts in honour of the Virgin, Christ or the Saints used as extra additions to the daily office or for a special occasion—the votive antiphon.

The texts of these votive antiphons are often sprawling and lengthy, often hyperbolic in their adoration of the Virgin, and often extravagant in the comparisons they make. For composers this meant an opportunity to write unfettered by the liturgy and to give free range to their style. They are therefore large-canvas works, often lasting more than ten minutes, and are a mixture of intricate solo writing set against sections for the full choir. The scope and scale of these compositions is a uniquely English phenomenon—no European composer of the period would ever produce such monumental music.

Thomas Tallis, who we currently assume was born around 1505, was brought up with the votive antiphon and his earliest compositions are in this form. Famously surviving the changes of direction imposed by four of the five Tudor monarchs, we can clearly see the development of this style including its restrictions as a result of Henry VIII’s reformation, its near-death experience under Edward VI and its brief resurgence under Mary I’s Catholic regime before it was finally discarded altogether during the reign of Elizabeth I.

This album contains all of Tallis’s votive antiphon settings—Ave, rosa sine spinis, Ave, Dei patris filia and Salve intemerata virgo being the earliest. Sancte Deus appears to belong to the time of Henry’s reformation, whilst debate still rages about when the sumptuous Gaude gloriosa was written. Suscipe quaeso Domine almost certainly belongs to the reign of Mary, and although its text is far removed from the earlier expansive homages to the Virgin, its style clearly shows the direction in which music was travelling. O nata lux is included as a coda, showing the brave new world which finally banished the votive antiphon and concentrated on settings of scripture, hymns and the Prayer Books.

Suscipe quaeso Domine is found in the 1575 Cantiones sacrae volume published jointly by Tallis and his younger friend and colleague William Byrd after they were granted a monopoly on the printing of music. It is a collection of Latin motets with each composer contributing seventeen pieces, perhaps to celebrate the number of years during which Elizabeth had ruled.

Much discussion has taken place about Suscipe quaeso Domine, a large-scale piece in two sections scored for seven voices. It has been suggested that this text, strongly penitential and rhetorical, could have been written and performed at the ceremony when Cardinal Pole (appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Mary Tudor) absolved England from schism in November 1554. Certainly it is full of passion and shows Tallis to have an unusually close relationship with his text. The harmonic shift and use of homophony at the word ‘peccavi’ (‘I have sinned’) juxtaposed with the upward yearning of ‘gratia tua’ (‘by your grace’) is certainly powerful, whilst the emphatic questions in the second part and the repeated ‘Quis enim iustus …?’ (‘For what just man …?’) demand the listener’s attention. In many ways the involvement with the text and the use of rhetoric seems to lead directly to William Byrd’s setting of Infelix ego from his own Cantiones sacrae of 1591, another intensely personal text which gives rise to an intensely personal response from the composer.

Tallis’s monumental votive antiphon Gaude gloriosa is another piece requiring some detective work. At first glance it appears to sit firmly within the pre-Reformation style. A setting of a lengthy and rambling text to the Virgin, it is similar to those set by the older masters such as Robert Fayrfax, Ludford and Taverner. What imitation is present in the piece is modest and short-lived and the whole makes its effect through its length (461 bars), wide vocal ranges and superb control of dramatic gestures. Contrast is created by juxtaposing sections for reduced forces with settings for full choir: all characteristics typical of the pre-Reformation style.

Yet there are good reasons for supposing a later date of composition. Compared with Tallis’s trio of early antiphons, Gaude gloriosa shows a considerable advance in confidence, structure and effect. Where the earlier pieces can seem rather sprawling, and in some cases appear to be the work of a composer learning his craft, Gaude gloriosa is sure-footed and eloquent. It is scored for six voices rather than the more usual five-part texture and sports divided tenors, a baritone and a bass part allowing a thicker sonority than is sometimes usual for an early sixteenth-century composition. The full sections contain little respite for the singers, with hardly a bar’s rest in any voice part, lengthy and demanding writing and a fairly constant exploitation of the upper register of the top part. In short it is bigger, thicker and more well-nourished than the earlier style. The sections for solo voices are the work of a mature composer, especially in the section making use of the treble and alto gimmells (the voices split into two parts) and, perhaps most tellingly, there are no duets (de rigueur in earlier pieces). It is almost as if this is Tallis remembering an older style, recreating a sound world banished by Edward VI.

One further point needs consideration: the text, an extended paean to the Virgin Mary, is deeply Catholic. It seems unlikely that such words would have been deemed appropriate in the latter days of Henry VIII, even when he was having a more Catholic phase. Yet this text in nine sections each beginning with the word ‘Gaude’ would have been just the sort of piece that Mary Tudor might have wanted to hear, one which could knit together both the old and new: a celebration of the world of her youth in its form and text and, through its very composition, a bedrock for her new Catholic order.

Sancte Deus belongs to the reign of Henry VIII and bears a striking resemblance to a piece of the same name by Philip van Wilder, one of Henry’s favourite composers. It has an unconventional scoring where the voice parts are required to do unusual things—the bass part sounding above the tenor part from time to time and the contratenor being almost as high as the triplex on occasion. Its text, in honour of Christ, suggests a piece of the late 1530s or early 1540s when devotion to the Virgin Mary was being discouraged. Rather like an older Marian antiphon it is in several sections but each section (and indeed the piece as a whole) is much shorter. Tallis makes use of fermata most usually associated with the mention of the name of Christ but not used for that purpose here. It also has a gloriously extended final Amen reminiscent of the traditional dramatic conclusions to the more expansive antiphons.

Ave, rosa sine spinis is an anonymous text of seven stanzas and is an extended meditation on Gabriel’s greeting to Mary found in St Luke’s Gospel. Its principal source is the Peterhouse Partbooks but it requires reconstruction (expertly handled here by Nick Sandon). The text is arranged cleverly: taking the first word of stanzas one and two, the first two words of stanzas three and four, and the first lines of stanzas five and six, Gabriel’s greeting to the Virgin is reproduced in full. Its rhyming scheme is pleasingly varied, using AABB for each four-line stanza. The text seems to have been a popular choice for Books of Hours and Nick Sandon refers to a glowing introduction found in the Enchiridion preclare ecclesie Sarum … (Paris, 1530):

This prayer shewe[d] oure ladye to a devoute persone sayenge that this golden prayer is the most sweetest et acceptabeleste to me in her aperynge she hadde this salutacyon et prayer wryten with letters of golde on her breste.

The music of Ave, rosa sine spinis is a considerable advance on that found in the rather jejune four-part Latin Magnificat, but it is not as sophisticated as Salve intemerata virgo. It is hard to place Tallis’s works in a chronological order, but of those left to us Ave, rosa sine spinis, Salve intemerata virgo and Ave, Dei patris filia are among the most youthful. We can with certainty say that they must belong to the period before his return to London as a member of the Chapel Royal in the mid-1540s. Tallis has learned his craft well, having a judicious mixture of sections for solo voices set against full-choir writing and an easy, fluent way with melody. Harmonically it is rather conservative, nearly always cadencing in D minor, but he does venture further abroad in the last section, visiting both the sub-dominant and dominant in the space of ten bars.

Ave, Dei patris filia is another of those sprawling Latin texts in honour of the Virgin which were popular in the pre-Reformation period. Tallis’s setting is obviously an early work as it would have had no place in any liturgies after the death of Henry VIII. It bears a close resemblance to a setting of the same words by Robert Fayrfax and it seems as if the young Tallis used the older composer’s work as a template for his own composition. David Allinson, whose edition is used on this recording, has not only reconstructed missing sections in the treble and tenor parts but has also undertaken extensive research into the similarities between the two settings: ‘The two works are in the same mode; the sectional disposition of voices, changes of scoring and cadence points are almost identical; and the head-motifs to each new section are very similar in shape and rhythmic character’ (Thomas Tallis Ave, Dei patris filia, ed. David Allinson—Antico Edition RCM20).

The length and style of Salve intemerata virgo, combined with its rambling, rather complicated text, clearly point to a piece for Henry VIII’s pre-Reformation years. The earliest manuscript for the antiphon is a single partbook dating from the late 1520s when Tallis would have been in his early twenties. He has obviously assimilated the work of Robert Fayrfax and others who excelled in the pre-Reformation style. As with the other early five-part antiphons, the piece is in two main sections (the first in a triple metre and the second in a duple) and involves an alternation of sections for solo voices set against dramatic contributions from the full choir.

As with Ave, rosa sine spinis and Ave, Dei patris filia, Salve intemerata virgo is a remarkable achievement by a young composer and even here there are signs of the characteristic harmonic turns and gestures that the composer was to bring to fulfilment in later antiphons. It is in the closing section of all three pieces that Tallis seems to emerge most clearly, each building to a sweeping Amen reminiscent of the final section of Gaude gloriosa (his final word in the antiphon tradition).

O nata lux is a setting of two verses from the hymn at Lauds on the Feast of the Transfiguration. It makes no provision for the singing of the other verses and is obviously a motet in its own right rather than a hymn for the Divine Office. Taking his earlier hymns as its starting point, it is homophonic throughout and perfect in its subtle harmonic and melodic touches and, rather in the manner of Tallis’s English anthems, it repeats its final section.

Andrew Carwood © 2018

Suscipe quaeso Domine [9:14]

Gaude gloriosa [17:50]

Sancte Deus [6:15]

Ave, rosa sine spinis [10:49]

Ave, Dei patris filia [15:45]

Salve intemerata virgo [16:06]

O nata lux [1:57]

Composer Info

Robert Parsons (c.1535-1572), Thomas Tallis

CD Info

CD CDA67874, CD CDA68250,