Program: #16-37 Air Date: Sep 05, 2016

To listen to this show, you must first LOG IN. If you have already logged in, but you are still seeing this message, please SUBSCRIBE or UPGRADE your subscriber level today.

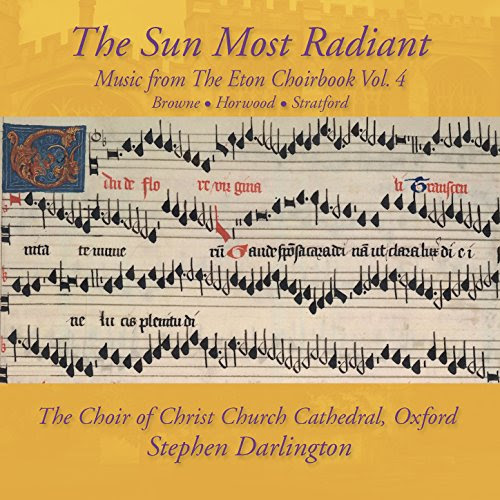

One of the worthiest projects in recent recording history is with Stephen Darlington and the Choir of Christ Church Oxford, and features mostly previously-unrecorded works from the Eton Choirbook. We turn to Volume 4 this week.

NOTE: All of the music on this program came from the recording The Sun Most Radiant. It features the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford directed by Stephen Darlington. It’s on the Avie label and the CD number is AV2359.

From the OXFORD TIMES: For the past few years, Christ Church Cathedral Choir has been on what musical director Stephen Darlington calls a “voyage of discovery” by recording long-forgotten music from the Eton Choirbook.

This magnificent tome, containing around 90 settings of texts about the Virgin Mary, was used by choristers at Eton College Chapel during the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

So far the choir has released three volumes of music from the Choirbook, all of which were nominated for Gramophone awards in the Early Music category.

A fourth volume, The Sun Most Radiant, is due for release on 9th September and focuses on three composers – John Browne, William Horwood and William Stratford. As with the previous volumes, this latest CD includes premiere recordings.

The original Eton Choirbook is in Eton College library, but Stephen proudly shows me a facsimile in his office.

“The actual book is about four times the size of this one,” he says. “The boys used to stand near the front of it, and you can see from the facsimile that the script is very clear. The adults used to stand behind. So everybody stood around the book so that they could all read it.”

Stephen’s interest in the Eton Choirbook was stirred when he heard the Stabat Mater by John Browne. “I thought, this is wonderful music, maybe it would be good to try doing it with this choir. It was also the challenge of doing this music with boys.

“Clearly at the end of the 15th century it was performed by boys, but I think the assumption in recent years was that it was too far out of the comfort zone for children to be able to do. But we do music by Taverner, who was the first director of music at Christ Church in the 1520s, and this is not long before that."

“I think we are the only all-male choir that’s recorded this amount of music from the Eton Choirbook. There may be one or two recordings of the Browne Stabat Mater, but there’s no other male choir that’s tackled it on this scale.”“I think we are the only all-male choir that’s recorded this amount of music from the Eton Choirbook. There may be one or two recordings of the Browne Stabat Mater, but there’s no other male choir that’s tackled it on this scale.”

So what, for Stephen, is the appeal of this music? “I always imagined that this period of music all sounded the same, so the real revelation for me has been that all these different composers have got different musical voices. The generic style is roughly the same, but the individual voices are very striking.

“Some of the composers write in a very harmonic way with a really strong sense of texture, so you get these wonderful passages where you have very widely spread chords, and then occasionally you get one particular part divided into two to add to the sonority.

“Then there are others who are fairly obsessed with intricate ornamentation and perhaps a slightly stronger sense of the linear approach.

“And of course it’s based on Plainsong foundation, so somewhere or other buried within the texture there’s always this Plainsong theme.”

With the fourth volume due out in two weeks’ time, Stephen is already thinking ahead to the next volume. “I’ve got a long list for a fifth volume and I’m quite hopeful we’ll do that in the coming year.

“We have other projects as well, but this one is particularly appealing because it is striking new ground.”

John Browne (fl. c.1480-1505): Salve regina I

Salve regina II

William Horwood c.1430-1484): Gaude flori virginali

William, monk of Stratford (?fl. c.15th-early 16th c.): Magnificat.

From Stephen Darlington: There are those who might wonder about the appeal of this liturgical music dating from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. I hope that this article will give you some small insight into the reasons for my enthusiasm and its suitability for a choir such as ours.

The Eton Choirbook is a remarkable music manuscript and represents a compilation of about ninety sacred works, all on texts in honour of the Virgin Mary. Of these, forty-three are complete, and twenty-one remain as fragments, in some cases susceptible to reconstruction. The copying began around 1500 and had been completed four years later, a remarkable achievement. The object of the collection was to provide a repertory of liturgical works to be sung in Eton College Chapel, primarily during the afternoon office of Vespers and the evening Salve ceremony. From its foundation in the early 1440s, there were clerks (skilful at singing to various degrees) and boy choristers. In fact, by the middle of the century, there were sixteen boy choristers in the foundation, exactly the same number as we have here at Christ Church. The complexity of the works preserved in the Eton Choirbook clearly demonstrates that these singers were virtuoso performers, particularly so during the fifteen-year tenure of Robert Wylkynson, who was the instructor of choristers from 1500 to 1515.

Three composers are represented in this latest volume of Eton Choirbook recordings. Of these, by far the most significant was John Browne, who was clearly one of the most respected composers of his own time. Little is known about him except that he was originally from Coventry, and was elected King’s Scholar at Eton College in July 1467 at the age of thirteen. I have chosen to include three of the fifteen works of his which appear in the Eton Choirbook. The first Salve regina setting on the CD is scored in five parts: treble, alto, two tenors, and bass. In common with many Eton Choirbook pieces, the full choir texture alternates with passages for smaller solo groups and juxtaposes two lengthy sections, one in triple time (known as ‘perfect time’) and the other in duple time (known as ‘imperfect time’). In the case of this piece, each of these sections involves a complete statement of a cantus firmus, the duration of each being exactly the same. This cantus firmus (the plainsong melody which underpins the whole piece) is Maria, ergo unxit pedes which was an antiphon used on Maundy Thursday during the ceremony of foot-washing. The second setting of the same text employs a scoring of five parts but this time three tenor parts and two bass parts. The principle of the structure is the same as the SATTB setting, but based on a different cantus firmus, Veni dilectus mei. The text comes from a Psalm antiphon set for Matins on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and is used elsewhere by Browne, in his O Maria salvatoris mater. It is interesting to compare these two settings of the same text, the former richly scored and in places remarkably modern in terms of its harmony, the latter more austere and restrained, but brilliant in its manipulation of the more restricted vocal ranges.

A superficial glance at the structure and musical language of the Eton Choirbook compositions might lead one to suppose that they are all written in a generic style with little room for individual approaches. However, the reality is very different. Each of these composers has a distinctive voice. After all, when considering eighteenth-century symphonies and their exploitation of sonata form structure it is readily recognised that the style of Mozart is very different from that of Haydn. So, William Horwood’s setting of the text Gaude flore virginali reveals a composer with different priorities from John Browne. For example, there are passages of considerable rhythmical complexity, particularly in the final section where the text is ‘that these joys seven shall neither minish, nor also cease, but still continue and ever increase while the Father is in Heaven’. At other points, he is less harmonically adventurous than Browne with a weaker instinct for sonority. William Horwood had a rather different background from John Browne, having been Informator Choristarum at Lincoln Cathedral following a period as Master of the London Guild of Parish Clerks. His style certainly represents an earlier generation than that of John Browne. Horwood was one of many composers whose settings of the Magnificat are included in the manuscript. Amongst these is a setting for four voices by William Stratford, scored for two tenors and two basses. As was standard practice, polyphonic verses alternate with plainsong and the composer is skilful in varying texture, sometimes in two parts, sometimes in three, as well as the full four voices. Some of this music is rhythmically intricate and there is a delightful energy in the close imitation between all of the parts. This is a freely composed setting and is this composer’s only contribution to the Eton Choirbook. His real title was ‘William, monk of Stratford’. It is thought that he was from the Cistercian Abbey of Stratforde Langthorne, and he certainly represents the significant minority of composers who were associated with monastic communities, such as Canterbury College, Oxford.

That these Eton compositions should be so appealing to our present choir is not a surprise. After all we function in much the same way as the Eton College Chapel Choir would have functioned at the beginning of the sixteenth century. The choir is involved in the daily singing of the offices in the Cathedral and the regularity of this commitment and the skill required is not dissimilar to that of previous generations. It seems clear that the original Eton Choirbook, a copy of which can be viewed in Eton College Library, was used by the singers as an aide-mémoire. It is large enough to be seen by a group of singers, with the young boys closest to the lectern and the adults behind. But it is also clear from sources that much of the music was memorized and rehearsed in advance, exactly as we do these days. The challenge for us is to revive not only the text but also the spirit of this music which is so glorious in its variety and complexity. The project has been inspiring to all those who have been involved. When searching for a title for this latest release, a particular phrase from Horwood’s Gaude flore virginali stood out: ‘the sun most radiant’. I hope it is not too fanciful to suppose that the Cathedral Choir’s performances of this repertory are shedding light on a hitherto neglected repertoire, and also bringing it to life through the use of a choir so similar to that of the 1500s.William Horwood (c. 1430 – 1484)

3. Gaude flore virginali a 5 * (14.56)

William Stratford (fl late 15th – early 16th centuries)

4. Magnificat a 4 (19.45)

- See more at: http://www.avie-records.com/releases/the-sun-most-radiant/#sthash.MOLT4hbK.dpuf

Composer Info

John Browne (fl. c.1480-1505), William Horwood (c.1430-1484), William Stratford (?fl. c.15th-early 16th c.)

CD Info

AV2359.